Developmental Care Section

The information on this page is intended for health professionals reference and use only. If you are a parent or family member looking for information about treatment, please visit unit information.

1.0 Aim of guideline

To provide a framework to optimise individualised care in neonatal units based on the behaviours exhibited by neonates.

2.0 Scope of guideline

The guideline applies to all neonatal units and maternity units covered by Thames Valley Neonatal Network. This includes the following hospitals:

3.0 Guideline summary

- Cue-based care is an approach that recognises and responds to the infant’s behavioural cues and their state of arousal. This informs the adaptation of procedures, routines and the environment to facilitate the neurodevelopmental needs of the infant.

- Cue-based care supports an individualised approach where the required care is variable and is based on interpretation of the infant’s signals over the routine or rigid protocol-based approach to care where individual needs are not considered.

- Behavioural cues are defined as non-verbal and special forms of communication that newborns and young infants use widely, to express their needs and wants.

- These cues may include behaviours indicating an infant’s readiness to engage, demonstrate distress, hunger or sleep/wake states.

- The goals of cue-based care are to provide an environment that is both physiologically and developmentally supportive.

- All neonates should receive individualised care, based on the behaviours they exhibit. This can be achieved by adapting the environment and care giving approach to each baby, based on the cues they have displayed. The outcome should be a facilitation of the infant’s self- regulatory behaviours and reduction in the infant’s stress.

- It should be assumed that all infants display behavioural cues from their birth, even if these cues are more subtle and autonomic in nature.

- Accurate observation of these behavioural cues should occur prior to, during and on completion of care giving activities.

- It is the clinician’s responsibility to adapt the environment, care routines and procedures to support each individual’s unique needs.

- All parents should be guided to observe and understand their baby’s unique behavioural cues as soon as possible after the neonatal admission. This will enable them to offer sensitive caregiving, build their confidence as their baby’s primary caregiver and support the parent-infant relationship.

- All procedures (other than emergencies) should be carried with full consideration of the baby’s behavioural cues.

- Use of the NIDCAP 5 step dialogue can form the framework in how to approach and support a baby in any interaction.

4.0 Guideline framework

4.1 Background information

- Behavioural cues are defined as non-verbal and special forms of communication that newborns and young infants use widely to express their needs and wants. Early and appropriate interpretation of these behavioural cues by caregivers, is a vital piece of developmentally appropriate care, promoting infant organisation and enhancing optimal neuro-developmental outcomes.

- Identification of behavioural cues that demonstrate comfort, pleasure, sleep/wake states will facilitate physiological/behavioural organization.

- Evidence suggests that responsive caregiving informed by the infant’s behavioural cues has been found to support greater physiological stability, fewer days of ventilation, reduction in complications, earlier feeding readiness, shorter stay in hospital and enhanced parent-infant relationship.

- All procedures (other than emergencies) should be carried with full consideration of the baby’s behavioural cues.

4.2 Parent education and support

- It is a priority to provide parents with education and support as early as possible to identify and to respond appropriately to their infant’s behavioural cues.

- Parents/carers should be offered both individualised cotside and more generalized teaching and support on how to recognise their infant’s behavioural cues and make informed / appropriate choices about their care giving.

- Parents/carers should be encouraged to respond appropriately to their infant’s behavioural cues.

- Information / comments from parents/carers on their infant’s behavioural cues should be acknowledged and documented into the infant’s developmental and nursing care plans.

- Information booklets on behavioural cues should be offered to all parents/carers, within the first week of life and explanation of contents given: This should be recorded in the infant’s care plan.

4.3 Practice guidelines

4.3.1 Preparation for interactions / cares

- Plan and time interventions with the parent in relation to their availability and other interventions needed for the baby throughout the whole day/night.

- Delay handling if baby is in quiet/deep sleep. Cares and interaction is best when a baby is in a quiet and alert state, and demonstrating approach signals.

- Cluster care as tolerated to provide long periods of undisturbed rest.

- Prepare for the activity to ensure all equipment is ready to use to reduce stress on the baby through unpredictable touch/timing.

- Ensure external environment is calm – dimmed lighting, low levels of noise.

- Supportive measures should be put in place before carrying out cares, procedures or interacting with an infant, to promote the infant’s calm state. This includes swaddling and nesting to support midline position and containment (i.e. hands to face, foot brace support)

- Ensure dummy and breastmilk is available if required and appropriate for non-nutritive suck

4.3.2 During cares

- Encourage parents to be their baby’s primary caregiver wherever possible- taking the lead as they feel confident, being guided by their needs for support.

- Encourage the parent to use their voice with their baby as the predominant auditory input – staff to keep own voice in background.

- Gently rouse the infant prior to care giving activities. This will avoid sudden disturbance in sleep or movement. This can be accomplished by gently talking to the infant and using still, steady touch on a less-sensitive body area (e.g. back, top of head). The NIDCAP 5-step dialogue is a helpful tool to form the framework in how to approach and support a baby in any interaction. See parent leaflet.

- Handling/positional changes should be slow, supported in flexion and minimal. Turning of the baby should be in small increments with pausing between stages – Use of muslin swaddle is recommended. See Positioning and Handling Guideline for more specific information. Interventions should be observed and evaluated regularly throughout process, watching for the baby’s response or ‘cues’ to inform support needs.

- Individualise all additional stimuli (e.g. auditory, tactile, visual) as appropriate for baby’s gestational and postnatal age and medical condition.

4.3.3 Observing behaviours

- Recognise behavioural cues (signs of stability or stress, approach cues, coping/self-calming cues, stress / time-out cues) and provide or modify care as appropriate.

- When a baby displays organized or ‘coping /approaching’ behavioural cues, it is the optimal time to engage and carry out cares or potentially feeds.

- When a baby displays disorganized ‘defensive/ avoidance’ behavioural cues, responsively implement strategies to support. This may include pausing the activity to wait for the baby to stabilise and calm before continuing.

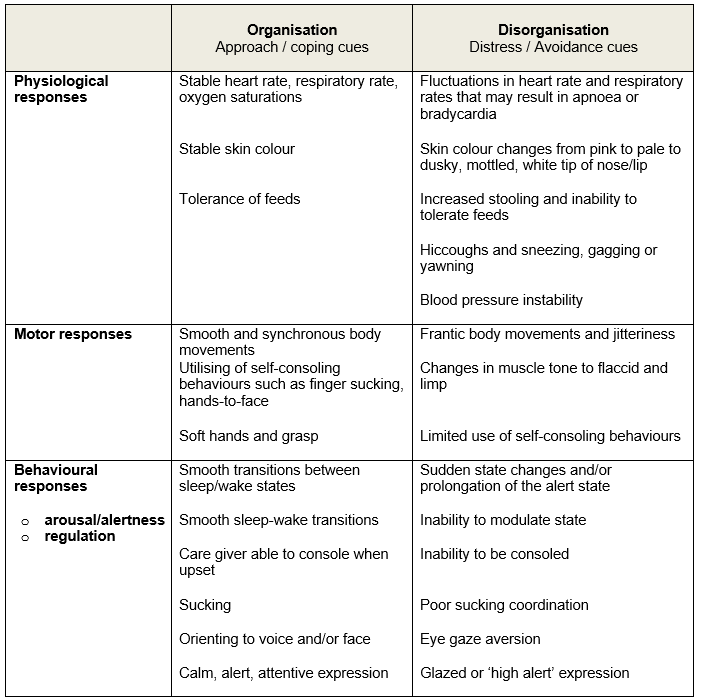

Refer to Appendix A for detailed information in recognising behavioural cues.

NOTE: Should the baby lose muscle tone, go floppy and move quickly into a sleep state during cares or procedures, immediately stop, provide containment, reduce external sensory stimulation and allow for recovery. This behaviour is termed ‘shut-down’ and it is the baby’s coping mechanism and physiological response to extreme overstimulation. They are not sleeping through the cares or procedure.

4.3.4 Strategies to support infant’s organisation for cares

-

- Assess the infant’s ability to manage clustered cares and adjust as necessary. If a baby is unable to cope with a particular cluster of care, then perform fewer care procedures in succession.

- The baby should set the pace for interaction, and engagement and disengagement cues need to be recognised and responded to appropriately.

- Have short containment breaks between interventions for recovery and observe the infant’s responses. This will avoid over stimulation and ‘disorganisation’

- Provide containment for baby if a change of position is required – use swaddling to support hands to midline and containment. Avoid sudden position changes.

- Minimise unnecessary light and noise during cares to avoid over-stimulation

- Facilitate self-consoling/calming behaviour through soothing interventions or comfort measures:

- Skin to skin

- Consider cares or procedures in a side-lying position rather than supine.

- Keep one hand on baby at all times, with a minimal amount of light, ‘on-off’ unpredictable touch.

- Help baby achieve hands to mouth position with full or half-swaddle

- Ensure containment (e.g. hand hugs, nesting, Zaky hand)

- Foot bracing (e.g. place hand on soles of feet, and bring hips and knees up)

- Provide opportunities for positive sensory tastes with breastmilk if available and use a dummy, or breast if appropriate, for non-nutritive suck (NNS).

- Encourage parents to interact with their baby by using a gentle soothing voice and/or ensure their baby can see their face to provide connection and reassurance.

- Speak gently and calmly to the baby.

- Pace activity according to the infant’s cues and communication.

- Recognise signs of stress and sensory overload and respond to baby’s disengagement cues by:

- stopping or pausing the activity providing support, to enable physiological recovery before continuing

- adjusting activity rate/speed

- modify positioning as needed – side lying often allows for better baby’s self-regulation.

- Providing appropriate still touch or a containment hold,

- Offering dummy and breastmilk, or non-nutritive sucking opportunities at the breast if appropriate

- Offering finger to grasp

- Reducing light and noise in the immediate environment.

4.4 Documentation

- Assess the infant’s response to care giving activities or procedures to identify those behavioural signals that indicate stress, discomfort, hunger or pain in each infant and document your action or plan.

Note: Disorganised behaviour may occur following activity.

- Document the infant’s stressors/behavioural cues and the modifications made to care routines and procedures.

- Identify those behavioural signals that demonstrate comfort, pleasure, sleep/wake states and physiological/behavioural organisation in each infant. Document your findings.

- Document those interventions that promote comfort – see Comfort measures and Developmental positioning protocols.

- the environmental and physiological strategies used to facilitate these coping/ approaching behavioural cues should be documented in the baby’s individualised developmental care plan, nursing care plan and medical notes, so that others can use this information to individualise the baby’s care.

4.5 Specific Cares

- Refer to parent / staff handouts attachments outlining developmentally supportive strategies for specific cares. Included:

- swaddled bathing

- swaddled weighing

- side lying nappy changes.

- Refer to Mouth Cares Guidelines for detailed information regarding developmentally supportive practices.

5.0 Appendix A – Identifying Behavioural Cues

Organised: Coping / approach behaviours are those which an infant does when it is able to manage the interaction or activity and is in a receptive state for communication

Disorganised: Defensive / avoidance behaviours are those which an infant displays when it is stressed and either not enjoying or not able to cope with the demands of the interaction or the activity occurring.

Version Control

| Version | Date | Details | Author(s) | Comments |

| 3 | March 2018 | Quality Care Group | ||

| 4 | April 2023 | Changed title from ‘Behavioural Cues’ to ‘Cue Based Care’ | A Clifford, TVW ODN OT Lead | |

| Review Date: | June 2026 | |||

Document version

Version 4

Lead Authors

Thames Valley & Wessex Neonatal ODN Guidelines Group

Amanda Clifford, Thames Valley & Wessex Neonatal ODN Occupational Therapy Lead

Approved by

Thames Valley & Wessex Neonatal ODN Governance Group

Approved on

15 June 2023

Renew date

June 2026

Full guide

Link to download full pdf guideline

Parent leaflets to download:

Related documents and references

Altimier,L. and Philips, R. (2013) The neonatal integrative developmental care model; Seven neuroprotective core measures for family-centred care. Newborn & Infant Nursing Reviews. Vol.13 (1), pp, 9-22.

Als, H., & McAnulty, G. B. (2011). The Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) with Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC): Comprehensive Care for Preterm Infants. Current women’s health reviews, 7(3), 288–301. https://doi.org/10.2174/157340411796355216

Anderson. P et al (2010) Early Sensitivity Training for Parents of Preterm Infants: Impact on the Developing Brain. Pediatric Research, Vol. 67 No. 3 pp 330-335.

The Australasian Nidcap Training Centre (2021, March 23) The Five Step Dialogue. Facebook https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=201520481739516

Brazelton.TB (1973) www.brazleton-institute.com Brazleton Newborn Behavioural Assessment Scale.

Blackburn,S. (1998) Environmental impact of the N.I.C.U. on developmental outcomes. Journal of Perinatal Nursing,Vol 4, pp42 – 54.

Bliss. (2006). Look at me – I am talking to you. Watching and understanding your premature baby. London: Bliss. Retrieved from: https://shop.bliss.org.uk/shop/files/Lookatme2019WEB.pdf

CUH (2015) Supporting and comforting your baby. Cambridge University Hospitals. www.cuh.org.uk/rosie/services/neonatal/nicu/developmental_care/support_comfort

Coughlin, M. (2017) Trauma-Informed Care in the NICU. Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines for Neonatal Clinicians. New York: Springer.

Edraki, M., Paran, M., Montaseri, S., Razavi Nejad, M., & Montaseri, Z. (2014). Comparing the effects of swaddled and conventional bathing methods on body temperature and crying duration in premature infants: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of caring sciences, 3(2), 83–91. doi:10.5681/jcs.2014.009

Fern D., Graves., L’Huilier M. Swaddle bathing in the newborn intensive care unit. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev 2002; 2(1): 3-4.

Gardner.S and Lubchenko.L.O (1993) The Neonate and the Environment: Impact on development. In Merenstein, G.B and Gardner.S.L, The Handbook of Neonatal Intensive Care, 4Th Ed, Mosby, St Louis.

Hall K. (2008). Practicing developmentally supportive care during infant bathing: reducing stress through swaddle bathing. Infant, 4(6), 198–201. Retrieved from https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.napier.ac.uk/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=105584815&site=ehost-live

Hannah.L (2010) Awareness of preterm infants’ behavioural cues: a survey of neonatal nurses in three Scottish neonatal units. Infant. Vol 6, pp 78-82.

Hawthorne.J (2005) Using the Neonatal Behavioural Assessment Scale to support parent-infant relatinships, Infant, Vol 1, no6, pp213-18.

Hawthorne.J and Savage-McGlynn.E (2013) Newborn behavioural observation: helping fathers and their babies. Perspective- NCT’s journal. P7-8

Kenner.C and McGrath.J.M (2004) Developmental care of newborns and Infants.

A guide for healthcare professionals, Mosby, St Louis.

Maguire C.M, Bruil.J, Wit.J.M, Walther.F.J (2007) Reading infants behavioural cues: An intervention study with parents of premature infants <32 weeks, Early Human Development, Vol 83, No 7, pp419-24

McAnulty GB, Butler SC, Bernstein JH, Als H, Duffy FH, Zurakowski D (2010) Effects of the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) at age 8 years: preliminary data. Clinical Pediatrics, 49(3), 258–270.

Melnyk BM, Feinstein NF, Alpert-Gillis L, Fairbanks E, Crean HF, Sinkin RA … Gross SJ (2006) Reducing premature infants’ length of stay and improving parents’ mental health outcomes with the Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment (COPE) neonatal intensive care unit program: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics, 118(5), 1414–1427.

Milgrom J, Martin PR, Newnham C, Holt CJ, Anderson PJ, Hunt RW … Gemmill AW (2019) Behavioural and cognitive outcomes following an early stress-reduction intervention for very preterm and extremely preterm infants. Pediatric Research, 86(1), 92–99.

Raineki, C., Lucion, A.B. and Weinberg, J. (2014). Neonatal Handling: An Overview of the Positive and Negative Effects. Developmental psychobiology, [online] 56(8), pp.1613–1625. Available at:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4833452/ [Accessed 14 Feb. 2021].

Warren,I.and Bond C (2010) Guidelines for infant development in the Newborn Nursery 5th Ed. Winncott Baby Unit, London.

Tedder.J (2008) Give them the HUG: An Innovative Approach to Helping parents Understand the Language of Their Newborn. The Journal of Perinatal Education, Spring, V.

Implications of race, equality & other diversity duties for this document

This guideline must be implemented fairly and without prejudice whether on the grounds of race, gender, sexual orientation or religion.